Backs to the Wall

22% interest rates and the farmers who pushed back

By Mel Luymes

To many of our Rural Voice readers, the early 1980s are a time they would rather forget. Record-high interest rates and low commodity prices led to an incredibly tense decade that took its toll on families and relationships, and it saw 13,000 Ontario families walk away from their farm dreams. It was also a time when communities were ignited with activism and protected their farm neighbours from foreclosure through farm gate defense tactics, penny auctions and public protests.

The economic wheels had been set in motion more than a decade earlier, with massive public spending, including agricultural subsidies, and high inflation rates. In the early 1970s, the U.S. abandoned the gold standard, sold its grain reserves to Russia and supported Israel, resulting in an oil embargo and skyrocketing energy prices.

All of this had led to farmers finally making some good money in the 1970s. USDA Secretary, Earl Butz, famously told farmers to “plant fencerow to fencerow” and to “get big or get out.” The banks also encouraged farmers to buy more land and livestock – they were happy to give out massive loans – and so there was a growing surplus of food, and many farmers took on a lot of debt.

When the U.S. Federal Reserve put the brakes on the Great Inflation by jacking up interest rates in 1979, farmers hit the windshield. Interest rates impacted all households and businesses alike, but farmers were in an especially precarious position because they had (and still have) significantly higher debt-to-income ratios than other parts of the economy. And as farmers’ debt payments were going up, their income was going down.

“It didn’t impact every farm equally,” says Jack Wilkinson, who was highly involved in the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA) at the time, and would later go on to Chair the OFA, the CFA and even the International Federation of Agricultural Producers. Areas like Grey-Bruce and Eastern Ontario, were hit earlier and harder than others, says Wilkinson, so those who weren’t as impacted at the beginning, said that these farmers had done it to themselves, a “self-inflicted wound.” This made tension within the provincial farm organizations and led to more difficulty driving protests and lobbying efforts at the provincial level in the early days.

The first protest was perhaps in late 1979 when interest rates first spiked. Bruce and Grey County beef farmers brought Big Bruce, the 15-foot-tall Hereford bull (statue) now in front of the municipal office in Chesley, to Queen’s Park, recalls Carl Spencer, a Grey County beef producer near Tara. He remembers that the Minister of Agriculture at the time, Lorne Henderson, parroted an “inspirational” message that was common in those days, “tough times don’t last, but tough farmers do.”

After some time of listening, Spencer recalls that Harry Biermans (Sr.) threw his hands in the air and let out a big roar. He yelled in his Dutch accent, “We’ve listened to this kind of bullsh*t for way too long and we’re not going to listen to it anymore.” And he turned around and walked away, with the rest of the farmers following him. “And the Minister of Agriculture was left talking to himself,” laughs Spencer.

Allen Wilford was a Grey County farmer that was hit early. He went on to become highly engaged in the activist movement in the County, and across North America. He wrote a book about the experience, Farm Gate Defense, in 1983 and he later went on to get a law degree in 1991. His book outlines the farm crisis, the development of the Farmer Survivalist organization and its key players.

“Someone ripped me off for a quarter of a million dollars,” it begins. Wilford read the fine print of his loans and was determined to prove that the floating interest rates that banks were charging him were illegal. Eventually, he did.

“It didn’t matter if you were a large farmer with expensive equipment or a small farmer with no equipment, or whether you were young or old,” writes Wilford. “It only depended on where you were when the gun went off.” Land values in Grey and Bruce County dropped by half nearly overnight, he writes, and at one point, his interest rates were 24.75 per cent. With corn prices and cattle prices low, his bank began to dictate how he would run his farm (into the ground).

Even though they had simply been following the market signals to expand, with the encouragement of the banks and governments alike, the farmers who had recently expanded when the gun went off were painted as poor managers. And while Massey-Ferguson received a government bail-out (1981), farmers received foreclosure notices. There was a great deal of shame and secrecy; there was domestic violence, divorce, and suicides. “There were a lot of farmers that were hurting, but were not letting on at all,” says Spencer.

Farmer activism

Bruce and Grey County farmers organized. Hundreds of farmers gathered in a local hall and discussed the issues, eventually deciding they should bring their tractors to Owen Sound. Carl Spencer remembers calling farmers to attend and admits that he had to tell some white lies about who else was attending in order to get people to come.

“People were worried they would be protesting alone,” says Spencer, “so I told them that so-and-so was going before they would agree.” Still, when the day came for the protest in October 1981, they hoped there would be a critical mass.

Many parked their equipment in a field just south of Owen Sound the night before. Allen Wilford was supposed to be bringing more from the Allenford area, George Bothwell with more from the east, and another contingent would come from the west.

“I said to a local dairy farmer, you’ve got this big tractor with the blade for silage, you lead the way and if there is a cop car in the way, you can move it for us,” laughs Spencer. In the end, he led the way down into Owen Sound himself and was relieved to see farmers coming in from the other three directions like they had said. They arrived there at seven in the morning and parked between 8th and 10th street for the morning, meeting with bankers and the media. Spencer says the people and businesses downtown were so welcoming to the farmers that they decided they shouldn’t overstay their welcome.

In December, in a hall in Kilsyth, the Grey-Bruce Farmer Survivalists were officially born, with a cool-headed, well-respected Carl Spencer elected as President. That was also the month that a loaded manure spreader parked outside a bank in Port Elgin in case the bank manager couldn’t come to some agreement with a farmer. While no one emptied the spreader that day, bags of manure and spreaders would come to be used as a common tactic over the following years.

Brian and Gisele Ireland had recently expanded with a new 100-sow barn in Teeswater when the gun went off, and they were at risk of losing it all. The Rural Voice caught up with the couple at their kitchen table to discuss their experience. Brian pulled out his wallet and sorted through it, handing a worn card across the table. It was his membership card from the Canadian Farmers Survival Association, and signed by a dear friend, Tom Shoebottom (1942 – 2021).

In those days, if a farm needed help, it could call the Farmer Survivalists; they would rally, calling fellow supporters and neighbours often in the middle of the night through formal or informal telephone lists.

The Rural Voice caught up Carl and Shirley Spencer to discuss their experiences in the farmers’ movement. Carl Spencer had bought the farm from his mother after his father passed away in a farm accident in 1966; he married his friend’s younger sister Shirley, who went on to be a nurse. Through some luck, by 1979 their debt-to-asset ratio was not as dire as most farmers. Still, Spencer devoted years to the Farmer Survivalists and spent hours every day on the phone, talking with banks, organizing neighbours. He was glad to have a really good man helping him with the farm during those days. Carl believed it was wrong that interest rates could be charged like that, essentially making farmers pay for an economic problem the governments and banks had created themselves.

The first farm gate defense was for Marvin Black, the Spencers neighbours. When the Black’s ambitious son wanted to expand the business in his late 20s, the bank suggested they give him a million-dollar loan, which he gladly accepted. It soon came crashing down when interest payments got too much and when the Survivalists gathered at Marvin’s place, they had to think of something. In the end, they all went home with his equipment, so there was nothing for the bank to take. Carl Spencer remembers he took home a 1066 tractor, which was bigger than anything he had at the time. He also took a nice new harvester. “I used it for a week or two chopping haylage, now that I think about it,” he laughs.

Black would sell cattle without telling the banks, and when their staff came to count them, he would pour them a few drinks in hopes they wouldn’t notice that he ran the same cattle through the chute a few times. He even moved the same cattle to the next farm to pull the same stunt while they went back into the house to warm up. But Black’s trick only worked for so long before it caught up to him.

For Allen Wilford, it was George Bothwell who first asked him if he would attend Marvin Black’s farm gate defense in 1981 and that led to years of organizing such interventions. Neighbours would come to the targeted farm to “hunt groundhogs on the front lawn” while the banker was there, but most often they wouldn’t bring their guns. Instead, they would try other sorts of mischief to stall a foreclosure in hopes of saving the farm. They would block entrances and exits with their vehicles, tie equipment together or remove the tongues so they couldn’t be moved off the property. Sometimes they relocated equipment and hid them in the bushes or in plain sight with their own, or moved some livestock off the farm and fed them in neighbouring barns. There was even a story about a drainage plow that cut a trench at the laneway so that no vehicles could go in or out. (Talk about a “last ditch effort”!) The farm gate defenses and Survivalists were associated with red bandanas worn around their necks; it was a symbol used in the farmers movement across the world at that time.

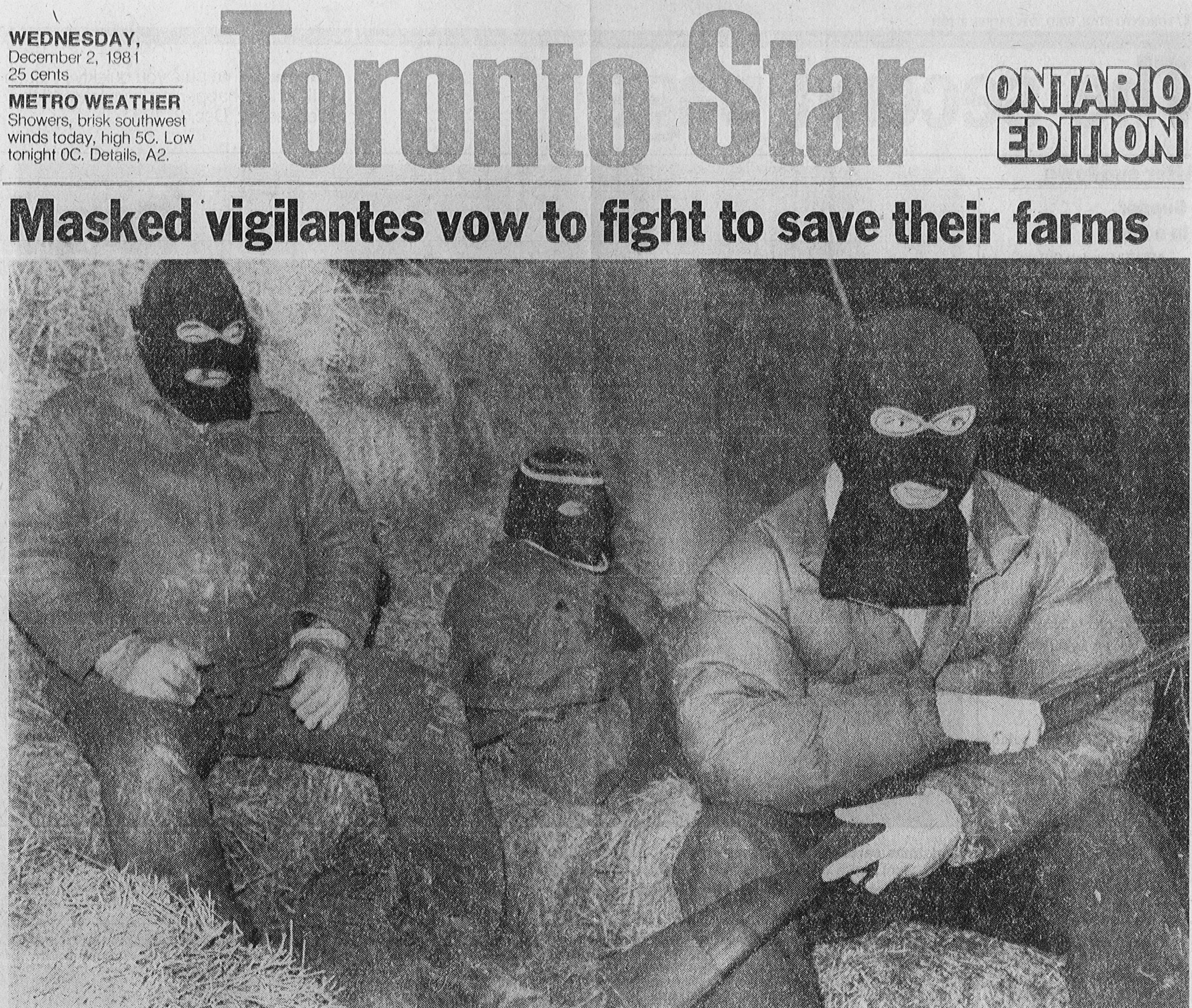

“There was a photo in the papers and tabloids of farmers wearing masks and holding guns,” says Gisele, referring to a photo that made the front page of the Toronto Star in December 2, 1982. “My friend called me and said, please tell me that isn’t Brian,” she continues. While Brian didn’t confirm or deny it was him in the photo, Gisele laughs that Brian wouldn’t know what to do with a gun if someone gave it to him.

“I know who is in the photo,” says Carl Spencer, with a sly smile, “but I’ve never told a soul.” He was part of the group that invited the out-of-town press to a barn on a property without a house. The rumour was that there were vigilantes in Grey-Bruce, and even though there weren’t, the group decided to stage some for the benefit of the media. Spencer says they couldn’t call Jim Algie from the Owen Sound Sun Times who was following them closely, because he would recognize their voices, so that’s why they called reporters they didn’t know.

They gave them the photo that would help spread the story about the Farmer Survivalists. The stories of activism and Grey-Bruce made headlines across the province, and one particularly sympathetic reporter was Gord Wainwright, from the London Free Press, say the Irelands.

The article accompanying the vigilante photo in the Toronto Star, by Fran Reynolds, quoted a farmer that summed up the sentiment: “We all stand to lose our farms. Our roots start in these farms and the soil, and if you pull them out, we’ll die. We’d rather die fighting than leave peacefully.”

In April 1982, the group brought 150 farm trucks to the Food Terminal at 3:00 am and blocked any shipments from entering, eventually creating traffic jams across downtown Toronto. They had politicians meet them there at the front lines and participating farmers were given some of the produce from the truckers, in solidarity. Shirley Spencer remembers well that morning she spent hours calling various media outlets in Toronto to cover the story, but many didn’t believe her. The Farmer Survivalists stood down just before lunch time that day, though they agreed that they left too early.

When 24-year old John Otto started farming, he bought a farm near Listowel and got his operating loan with TD in 1978; he remembers that he requested a fixed rate loan at eight per cent, but the banker disagreed. “I remember my stomach turned,” says Otto, he knew the loan wasn’t right. And five years later, when the bank said they would take everything, Otto called Allen Wilford, who was by then the President of the Farmer Survivalists.

February 9, 1983 was the day of the auction, with an auctioneer and the liquidating company there. “The bank didn’t really care what they got for the equipment, they were really after my father, who had guaranteed the loan with everything he had,” explains Otto.

Otto didn’t know what was about to happen, but the Farmer Survivalists did. They came by the hundreds to spoil an auction. When the auctioneer began, they threw snowballs at him until he got down, and that’s when Tom Shoebottom stepped up and ran it, only taking bids from Farmer Survivalists that were holding a special card. He sold $100,000 worth of equipment for $19.80.

Wilford had cut the phone lines to delay the police coming, but eventually they came and deemed the auction illegal. But it was too late; much of the equipment had been taken off the property and Otto’s neighbours had organized who had what.

The movement grew across Canada. There were a few hundred members in Grey-Bruce and likely a few thousand across the country

After Otto’s penny auction, Wilford was arrested on charges of theft and was detained in a Stratford jail. He used the opportunity to go on a hunger strike until MP Ralph Ferguson’s private member’s bill C653 – amending the Farm Credit Corporations Act – received its second reading. The strike lasted eight days, but it worked. Wendy Wilford was a force in the media, especially while her (then) husband was in jail, but she also took care of the farm while Allen travelled across Canada and the U.S. during that time.

The “penny auction” hadn’t been used since the 1930s, and the show of force made the banks back down on farm foreclosures for nine months, says Otto. He will never forget the cars lined up all the way down the road, as far as the eye could see. “It was like Field of Dreams,” says Otto, still moved by the show of support he received that day, and from farmers that came as far as Chatham. Otto sold his steers in 1984 and kept farming until 1989.

When the Otto family went to church that next Sunday, they got a cold reception from a few members. Similarly, several farmers in the OFA had disagreed with the penny auction, and it took months before they changed their mind about it.

On a few occasions, after banks had foreclosed and started renting out their fields to local farmers, others came in with tillage equipment to tear up crops after they had been seeded. “That didn’t make the news,” says Carl Spencer, “but it did help slow down the banks from shutting farms down.”

While Grey-Bruce was a hot spot of activism, so was Eastern Ontario and eventually, activism was organized on a provincial level. Wilkinson remembers the impressive effort and solidarity, but also the unease. The phones of farm leaders were tapped, and the police always knew what they were up to. Farmers don’t want to break the law, he emphasizes, but they felt they had no choice. Still, to this day, many farmers won’t name any names of the people who crossed a line. Gisele Ireland says she and Brian had been suspected for releasing a load of piglets in the legislature around that time. She denies that it was them, but adds, “it was a great idea, and I wish I had thought of it.”

Wilkinson credits the success of the lobby effort to the (large) structure of the OFA at that time; every month, delegates from every corner of the province came to Toronto, so everyone knew what was going on. When they really needed to lobby on an issue, each MP or MPP would get a knock on their door when they came back to their home riding that weekend.

Spencer recalls that he dressed up in his best suit and joined with Bill Wolfe and Leonard Calhoun to visit all the major banks in Toronto. From hot-headed protests to cool-headed conversations, the movement of farmers did everything they could. Looking back, perhaps it was a wonder that no one killed bankers, and there were certainly a few instances of that in the U.S.

Local impacts

These were stressful days for bankers as well. Ron Anderson remembers the earliest days as the worst. It was new territory for banks, and they didn’t have protocol for handling non-payments or doing foreclosures. There were many younger bankers being directed to enter the properties of their friends and neighbours to foreclose, and it was a terrible time.

Brian Ireland recalls his banker was sent out to his farm at 5:30 one evening to collect more serial numbers from his farm equipment, but Ireland wouldn’t let him. They got talking. Ireland knew him as a great guy who wouldn’t miss a chance to bring his wife out to a barn dance and would attend every community event. He was only six months away from retirement and a pension, so he couldn’t quit his job at the bank. He became a recluse from the community and confided to Ireland that he drank a bottle of whiskey every night. The two caught up years later, and he was back to his old self again.

“They pulled the pin on my birthday,” remembers Ireland. “They said, we’re just calling to notify you that every pig cheque from hereon in comes to us.” So, he called the yard and had them ship the 86 hogs under Stan Zurbrigg’s number, the farmer who had sold him feed on credit. “The bank was just livid,” he says. At another point, the Irelands had qualified for a farmer assistance loan for $20,000 from the government at some point, but they never saw a penny of it; it went straight to the bank.

Brian and Gisele remember well the stress of those days. At one point, they and their four children were done with feeling so poor all the time. They went through every coin in their piggy banks and tore through the couch cushions, collecting enough money to order pizza for dinner that night, and they had it delivered.

“We were going to walk away,” says Ireland, but then on the Sunday night before they were going to lose the farm, George Bothwell called him up with an idea. He had set up a committee and was going door to door to the Ireland’s neighbours and friends to try to raise the money to save the farm.

“Most of the people that threw in a thousand bucks were pretty near as hard up as we were, but they raised the $200,000,” he says. Thanks to the overwhelming support of their community, they got a bridge loan to a new mortgage with the North Huron Credit Union in Wingham (now Libro) and were able to pay everyone back within a few months, with five per cent interest. Many didn’t want to be paid back the interest.

“That experience made the whole thing hurt less,” says Gisele, and says it was a turning point for them. They were able to sell some land, stay on the 100-acre home place and they went on to start Teeswater Agro Parts, which serves their community well to this day. The family are forever grateful to the friends who pulled them through, they say they wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for them.

Farm women organize

Gisele Ireland wrote a book, The Farmer Takes a Wife, in 1983, about the results of a 31-page survey of 600 farm women of Grey and Bruce Counties, initiated by the Concerned Farm Women, a local group. Gisele did a beautiful job of capturing the lived experiences of farm women and an illustrator outlined some of the statistics captured from the survey. Eighty-six per cent believed that the farming community was worse off than in 1976. Seventeen per cent of respondents believed they would lose all or most of their farms within the year. And, according to the statistics, they were right.

Women’s movements were about more than just the female experience of the debt crisis, but about their property rights. “Farm women didn’t realize they were personally responsible for their husband’s farm debt,” says Maria Van Bommel, who was a leader of the Ontario women’s movement in the 1980s. Women who worked off the farm were having their wages garnished by the banks, she says, and yet they had no legal right to the farm as men were often the only ones named on the farm property title. “If you are paying the debt, you need to have a corresponding asset,” she says.

In November 1984, the Concerned Farm Women joined with two other farm women groups that had developed in Eastern and Southwestern Ontario for a conference they called Turning Point. The group lobbied and worked through the family court system to change legislation and win many the property rights that farm women have today. Another key leader was Dianne Harkin (1934 - 2022), from the Women for the Survival of Agriculture in Eastern Ontario; she recently published a book about that time, They Said We Couldn’t Do It – The Story of a Quiet Revolution.

“Women would have found this out eventually if they had gotten a divorce,” Van Bommel continues, but divorce was so uncommon back then. Farm husbands had a stoicism towards their work and their relationships, and the same was true of farm wives, she says.

This was the beginning of Maria van Bommel’s involvement in farm organizations. She went on to be one of the first female directors of the OFA and to a career in politics as an MPP from 2003 to 2011. She believes that the 1980s was a turning point and, since then, more women have been involved in farm organizations, as they should be.

Farm crisis winds down

By late 1985, there was a moratorium on foreclosures by the Farm Credit Corporation (FCC), but earlier that year, the Van Bommels had walked away from their farm. In 1986 the Farm Debt Review Act came into force, establishing Farm Debt Review boards in every province, and that was the year that Jack Wilkinson left his farm in Lambton County to farm in Northern Ontario.

Perhaps it was too little, too late, wonders Wilkinson. Others agreed that the damage had been done by that point, and that while the Farm Debt Review Board helped people wind down their businesses, it wasn’t a real solution to the issues in any case. It continued to review farms as individual cases of mismanagement, instead of symptoms of a “systemic evil,” Wilford argues in his book.

Eventually the interest rates caught up with most farmers. One of them, much later, confided in Brian Ireland that at first, he thought the Farmer Survivalists were crazy, and he didn’t support them at all. But later, when he came so close to losing his farm, he saw the importance of the work they did for other farmers. “He was crying when he told me that,” says Ireland. “He said he just had to tell someone how bad it had got for him.”

Ireland was a listening ear and helped many farmers through their darkest days. He took the bank’s advice and got an off-farm job as well. He worked for the Queens Bush Rural Ministries, which started in 1987 to provide counselling, support and connections to struggling farm families. Driving across Huron, Perth, Grey, and Bruce, he served his farm community for 12 years, working closely with Allen Emerson, who had legal savvy that helped farmers. Carl Spencer served on the board of the organization for nine years, two as Chairman, and says that Ireland did an incredible job helping farmers and farm families during that time.

Keith Roulston and Anne Chislett wrote a play that first ran at the Blyth Festival Theatre in June 1986, called Another Season’s Promise. It was about a family who had expanded their farm just before the gun went off. The farm crisis unfolded on stage in the kitchen of the Purves family, including a house raid by the OPP to seize the farm books (which had happened to several farmers during the crisis).

Those that watched the play remember it vividly; there was not a dry eye in the house as the farm community had its tragic story reflected back to them. In Act Two of the play, the Purves family continues to rent and work on the property, but the farm is owned by a foreign-owned company named Futura. It didn’t take much for theatre goers to connect the dots with Canadian Agra and the thousands of acres the company bought when farmers and farmland values were at their lowest. The company rented out the houses, but there was often a stigma attached to living in one of those homes, and so they opted to bulldoze them (and the barns) to save on property taxes.

Looking back, the 1980s changed the rural landscape and it served to make-or-break farmers. It would be rare for a farm family to make a living just on 100 acres like they used to, so perhaps it was inevitable for farmers to either “get big or get out.”

Some will argue, like Allen Wilford did, that the 1980s were no accident.

“The banks were continually talking about failure, and the farmer felt guilty enough as it was,” writes Wilford. “It finally got to the point where farmers realized their failure was a result of deliberate policy; that they’d gone broke, not because government policies failed, but because government policies had worked.”

In other words, while farm groups lobbied for the relief that would keep farmers in business, there were politicians and others that believed these were instead the bitter medicine that would lead rural Ontario to a prosperous future. Whatever the means, farm expansion would come at a cost, and not only the economic cost to the farmer taking on the debt, but the social cost of neighbours losing their family farms and communities losing businesses.

Forty years later and the world has changed, says Jack Wilkinson. The inflation rate is back to normal after a global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but the threat of overproduction still looms, The E.U. has modified its farm subsidies from production to environmental support; however, we have production areas in South America that are much stronger than before. He hopes that farm organizations and governments stay vigilant to prevent another crisis.

Frances Anderson, who spent 37 years in ag reporting for the Ontario Farmer, reflects: “The saddest legacy was that farmers discouraged their children from farming because they couldn’t see a future in it.” And she worries that the current generation of young farmers, who have had mostly decent commodity prices and interest rates, take their farm lifestyle for granted and credit their own management, when at least half of their success is due to good timing, and (at least until now) relatively stable geopolitics.

Could it happen again? Hindsight is 20/20, they say. Perhaps farmers could have seen the writing on the wall in 1975, but they didn’t. If every 50 years we see a massive and painful economic restructuring, are we due for another one in 2030? We hope that we learned lessons from the past to avoid repeating history, but only time will tell. ◊

The author would like to say a huge thank you to both Shirley Spencer and Debbie Otto who kept newspaper clippings from the time. And to all who attending the "penny auction reunion" in August 2025. If anyone has more thoughts to contribute about this time, please get in touch! [email protected]